Thylacine mystery solved in TMAG collections

Ground-breaking new research has solved one of Tasmania’s most enduring zoological mysteries: what happened to the remains of the last known thylacine, or Tasmanian tiger?

In a paper soon to be published in Australian Zoologist, researchers Robert Paddle and Kathryn Medlock reveal that the remains came into the collections of the Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery (TMAG) in 1936 but had until now remained unidentified.

The last known thylacine (Thylacinus cynocephalus) died in the Beaumaris Zoo on the Queen’s Domain, Hobart during the night of 7 September 1936.

However, Dr Paddle, a comparative psychologist from the Australian Catholic University, and Ms Medlock, Honorary Curator of Vertebrate Zoology at TMAG, have discovered that this thylacine was not the animal previously identified as the last thylacine in photographs and film – the much photographed and filmed specimen was in fact the penultimate thylacine.

Dr Paddle said the actual last thylacine, or endling of the species, was an old female animal that had been captured by trapper Elias Churchill from the Florentine Valley and sold to the zoo in the middle of May 1936.

“The sale was not recorded or publicised by the zoo because, at the time, ground-based snaring was illegal and Churchill could have been fined,” Dr Paddle said.

“The thylacine only lived for a few months and, when it died, its body was transferred to TMAG.

“For years, many museum curators and researchers searched for its remains without success, as no thylacine material dating from 1936 had been recorded in the zoological collection, and so it was assumed its body had been discarded.”

Ms Medlock said the last thylacine’s arrival at TMAG was verified by the discovery of an unpublished museum taxidermist’s report dated 1936/37 that mentioned a thylacine among the list of specimens worked on during the year.

This led to a review of all the thylacine skins and skeletons in the TMAG collection, and the subsequent discovery of the last animal.

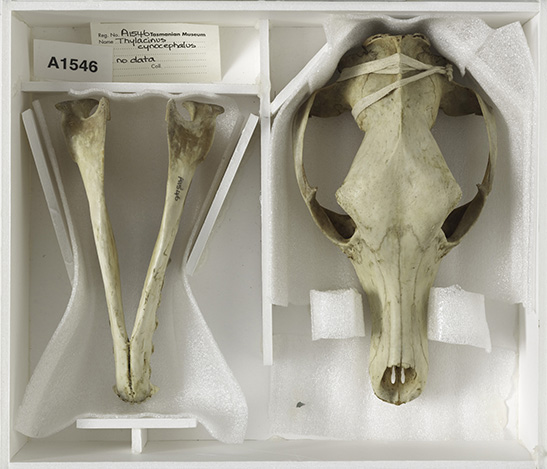

“The thylacine body had been skinned, and the disarticulated skeleton was positioned on a series of five cards to be included in the newly formed education collection overseen by museum science teacher Mr A W G Powell,” Ms Medlock said.

“The arrangement of the skeleton on the cards allowed museum teachers to explain thylacine anatomy to students.

“The skin was carefully tanned as a flat skin by the museum’s taxidermist, William Cunningham, which meant it could be easily transported and used as a demonstration specimen for school classes learning about Tasmanian marsupials.”

TMAG Director Mary Mulcahy said the last thylacine’s tanned flat skin and disarticulated skeleton, still attached to the five cards created for the education collection, were now on display in the museum’s thylacine gallery.

“It is bittersweet that the mystery surrounding the remains of the last thylacine has been solved, and that it has been discovered to be part of TMAG’s collection,” Ms Mulcahy said.

“Our thylacine collection at TMAG is very precious and is held in high regard by researchers, with the museum regularly receiving requests to access our mounted specimens as well as thylacine bones, skins and preserved pouch young.

“Our thylacine gallery is incredibly popular with visitors and we invite everyone to TMAG to see the remains of the last thylacine, finally on show for all to see.”

Dr Paddle and Ms Medlock said that with the identification of the thylacine endling’s remains, and its placement on public display at TMAG, as a species the Tasmanian tiger may now appropriately take its place alongside the passenger pigeon and Carolina parakeet.

Bob Paddle and Kathryn Medlock’s paper will soon be available to download on the Australian Zoologist website.